We live in a world full of dystopian movies and books, drawn from the horrors of war, famine, and history. Where do these works of fiction draw their inspiration from? From what recesses of our mind do we create images of the living dead and fears of an enemy so great and powerful that any resistance would be futile? For many in Europe and all who have studied twentieth century history, the Nazi regime springs to mind as the embodiment of that horror and destroyer of all who opposed them.

Did the Nazis create, amongst other things, the concentration camp? We can understand efficiency and organisation—something for which Germany is well known—but when these skills are superimposed on a system that is designed to break the body and mind of the enemy, the result is terrifying. Is it possible that a regime known for its clinical barbarianism could have been inspired by a country like Canada—better known for its wheat fields, Rocky Mountains, and limitless opportunities?

Adolf Hitler was an artist and avid amateur historian before he became one of the biggest mass murderers in history. He was, along with millions of other Germans, a fan of the adventure stories of Karl May. Karl May’s books, still in print, have sold over two hundred million copies to date. May’s Winnetou novels detail adventures of a German surveyor (Old Shatterhand) and a noble Mescalero Apache. At the time, May was as popular as today’s J.K. Rowling or Stephen King. Hitler, as Fuehrer, is quoted (in Table Talk, a series of WWII monologues delivered by Hitler 1941-1944 recorded by Heinrich Heim, Henry Picker, and Martin Bormann) as saying “… I owe him [Karl May] my first notions of geography and the fact that he opened my eyes to the world. … I went on to devour at once the other books by the same author.” As Fuehrer, Hitler kept the entire May collection in his bedroom.

In Alan Gilbert’s article The Cowboy Novels that Inspired Hitler (in the Daily Beast.com), he quotes:

“Of Ukrainians, Hitler insisted, ‘There’s only our duty: to Germanize this country by the immigration of Germans, and to look upon the natives as Redskins.’ “

“To justify the slaughter of Poles, Hitler conjured North America: ‘I don’t see why a German who eats a piece of bread should torment himself with the idea that the soil that produces this bread has been won by the sword. When we eat wheat from Canada, we don’t think about the despoiled Indians.’ “

As a result of May’s works, Hitler was fascinated by all things connected to the North American “Indians” and the cowboys who tamed the Wild West. Of particular interest was the implementation of camps that contained the population of the Indigenous people. (In the United States, these holding areas are called Indian reservations; in Canada, they are called Indian reserves. Despite knowing they hadn’t reached India, Europeans continued to call Indigenous peoples Indians. Canadian legislation forces the continued use of this pejorative word by virtue of the Indian Act.)

When sifting through the archaeology of historical documents, it is impossible to point to any one action and say with certainty that Hitler did x because of y. What we can say is that he was drawn to the conflict of the American “Cowboy and Indian” and merged it with his twisted epic vision of an Aryan German Empire (aka Third Reich). For Hitler, it is difficult to say whether he drew any specific inspiration from Canada’s system of Indigenous containment. What is striking is how he adopted a similar methodology when processing prisoners in his Nazi camps as the Canadians employed in processing its Indigenous in their camps (ie. Indian Reserves combined with the Residential school system).

When Hitler sought to control the politicians and undesirables, he put them in concentration camps. At that time, there was no association with the death and genocide that we think of today. There was abuse in concentration camps as there is abuse in prison; there has always been and will likely always be. Concentration camps existed in Canada and the United States to intern the Japanese and Germans who might have been potential enemy combatants during the same war. The British in South Africa created concentration camps during the Boer Wars (1900-1902). This was just another name for a camp that was something less than a prison but more than house arrest or relying on the integrity of the person. It was the physical movement of people into a concentrated area to watch, educate, and discipline.

Although the United States government created concentration camps as early as 1838, the use of this method of internment became prevalent from the 1860s onwards as the borders of the United States moved ever westwards. The U.S. government referred to these concentration camps as Indian reservations. Reservations referred to land that the government had to set aside to house the ‘Indians’. Canada decided to force the assimilation of Indigenous people from its reserves. It concluded that basic education and training in physical work would make its Indigenous people productive members of Canadian society. Boys would be taught agriculture half a day and girls would be taught domestic chores half a day. The other half would be spent in the classroom. (The thinking was that they could increase labour without threatening the opportunity of European settlers.) In contrast, Nazi camps ensured that all able bodies were put to work—making toys, shoes, counterfeiting foreign currency, as well as munitions.

From before Canada was formed in 1867, the colonial government decided to begin a systematic assimilation of the Indigenous people with the stated objective of ‘taking the Indian out of the Indian’. A boarding school system called residential schools was thought to be the most effective way of washing away the unwanted cultures, languages, and customs. Children were taken from their families and placed in these residential schools (for most, year round). They were not allowed to speak their language, act ‘like Indians’ or even wear their familiar clothing.

It is difficult for us to imagine a world without the harrowing images of the Nazi concentration camps. Broken bodies, walking dead, and sallow eyes in striped prison outfits fill our mind’s eye. Forced labour, strict discipline, and winnowing rations kept the prison population in check. Names were replaced with numbers. Identities all but ceased in the camps. When the Russian and Allied forces liberated these places of death and disease, the world saw a glimpse into the deepest horrors of its collective heart. This was an unthinkable existence perpetrated in and by a modern, liberal European country against its own citizens as well as those it saw as its enemies. This was war.

Since WWII, we continue to witness atrocities perpetrated by nations against others, but few of this scale. Today, we hear of bombings (suicide and otherwise), beheadings, and other medieval-like inflictions by one group over another. We deem these groups outlaws and rogue states and terrorists. This is also the face of war, just updated.

Concentration Camps of Canada, draws attention to both the realities of the reserves where the Indigenous of Canada live to this day as well as the efforts by Canada to forcibly assimilate its one-time allies. The residential schools were not happy places for their pupils. Sadly, the usual sexual abuses existed and these grab the headlines. But the horror was the institutional backing of a policy recently deemed cultural genocide by both the United Nations and Canada’s Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin. It was a time where corporal punishment was the norm and these schools applied it to the point where it was considered abuse even for the times. Children were stripped of their ‘Indian’ name and given a number or a Christian name instead. They were constantly beaten—for speaking a language other than French or English, for doing anything considered ‘Indian’, and for not conforming to the Church-administered curriculum. Eighty thousand survivors of this system are still alive today (the last residential school was only shut down in 1996). Broken from reliving memories, many testified of the horrors to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This commission published its report in 2015 where it concludes and agrees with the United Nations that Canada committed a sustained and systematic policy of cultural genocide. Where the Nazi camps lasted a little more than a decade, Canada’s continued for almost 150 years.

At the heart of the problem is poverty and a system that is too quick to give the benefit of doubt to those in power and too quick to dismiss concerns raised by those without.

Originally, Concentration Camps of Canada was envisioned as a text book with the main character (Migizi) demonstrating the multitude of injustices faced by Indigenous Canadians. Every element of Concentration Camps of Canada is based on the truth—gleaned from personal interviews as well as stories published by the official Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015. The project was then winnowed into a story for brevity. Written for non-readers, it moves quickly and touches on matters that will, hopefully, resonate beyond the pages.

The story of Canada’s residential schools does not carry the shame history ascribes to Germany’s camps—nor should it. It is a terrible tragedy inflicted on a people who were subsequently forgotten by the world. If that statement were true, this subject would be closed. The truth of the matter is that the misguided approach that manifested itself in residential schools remains alive today in Canada’s treatment of Indigenous children through the Child and Family Services agencies. At present, we watch but rarely see the on-going damage to an already shattered culture.

To quote from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s executive summary at page 37 ff:

“It can start with a knock on the door one morning. It is the local Indian agent, or the parish priest, or perhaps, a Mounted Police officer. … There was a big truck. It had a back door and that truck was full of kids and there was [sic] no windows on that truck.” Larry Beardy travelled by train from Churchill, Manitoba, to the Anglican residential school in Dauphin, Manitoba—a journey of 1,200 kilometres.

… Campbell Papequash was taken, against his will, to residential school in 1946. “And after I was taken there they took off my clothes and then they deloused me. I didn’t know what was happening but I later learned about it, that they were delousing me; ‘the dirty, no-good-for-nothing savages, lousy.’”

…Murray Crowe said his clothes from home were taken and burned at the school that he attended in north-western Ontario.

… Gilles Petiquay, who attended the Pointe Bleus School, was shocked by the fact that each student was assigned a number. ‘I remember that the first number that I had at the residential school was 95. I had that number—95—for a year. The second number was number 4. I had it for a longer period of time. The third number was 56. I also kept it for a long time. We walked with the number on us.’

[at page 101 of the TRC] Discipline was ‘too suggestive of the old system of flogging criminals’. Children were chained together. In at least one instance, a boy was chained to his bed and flogged by the principal.

Abuse was not unreported. As early as 1886, Jean L’Heureux, a recruiter for the Roman Catholic Church, was accused of sexual abuse. No charges were laid. Over time, the government ignored and dismissed claims from the Indigenous alumni as baseless.

The schools were meant to cost the Canadian government nothing—as the forced child labour would generate income and the poorly paid missionaries kept overheads low. This model soon proved unsustainable and schools received a fixed amount per child. The unintended consequences was an increase of students who were too young or too sick to attend officially. This compounded the deaths. Official figures admit around 3,500 children dying while in care but unofficial figures estimate tens of thousands of children buried in unmarked graves—not too dissimilar to recent revelations about a care home run by Catholic nuns in Lanarkshire where at least four hundred (400) children are thought to be buried in a field without any markings. Or Ireland’s Tuam mother and baby home where Catholic nuns buried nearly eight hundred (800) babies and young children who died in their care—all in unmarked graves.

The Royal Mounted Police apologised in 2004 for its role in the residential schools. In 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, issued a formal apology for the creation of the residential schools and the abuses carried out within it. All of the churches involved have apologised except the Catholic Church. The Pope has “… offered his sympathy and prayerful solidarity” for the Catholic Church’s role and abuses in the residential schools.

Nazis understood the role of their camps. On the surface, it provided a source of free labour, available subjects for their medical experiments, and a place to put dissidents without killing them outright (initially). The reality is that it formed a key component of Hitler’s strategy. His war was total—cultural, physical, and emotional. His objective was to cleanse Germany and the world of unwanted people (from Jews to Gypsies) and unwanted cultures. The camps have become synonymous with death but there were things worse than death—people being reduced to the living dead.

The consequence of the Nazis and WWII created a crisis of faith amongst Jews (and others). How could God allow such evil to be committed against his chosen people? Yet, three years after the last Nazi camp was liberated, the State of Israel was born.

For the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, the survivors have no land to return to. None of the reserves on which they live are theirs. Everything remains owned by Canada. They don’t even own their home on the reserve. Worse, they are not allowed by law to own their home or anything else on the reserve. For a policy that had its stated aim being assimilation, Canada failed to inculcate the most fundamental tenant of post-industrial modern existence—ownership and money.

War is all about subjugating your enemy’s will to your own. With the Nazis, everyone knew where they stood. With Canada, most of the world remains ignorant of the facts. There has been no Auschwitz-Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen moment in Canada where the world’s consciousness becomes aware of the plight of a people. No news reels would broadcast the images of troops liberating an emaciated people. Unlike Auschwitz-Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen, there would never be a liberation of Canada’s concentration camps.

-----------------------

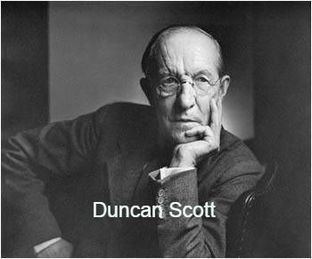

*** If you are wondering who Duncan Scott was (pictured above), here is an exerpt from Wikipedia***

Prior to taking up his position as head of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1905 Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners sent to negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario. Aside from his poetry, Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932.

Even before Confederation, the Canadian government had adopted a policy of assimilation under the Gradual Civilization Act 1857. One biographer of Scott states that:

The Canadian government’s Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red' man ought to become just like the 'white' man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: 'The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.'... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the 'Indian problem,' and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize' them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government’s goal. Scott ... would later pat himself on the back: 'I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.'[5]

while Scott himself wrote:

I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.[7][8]

Did the Nazis create, amongst other things, the concentration camp? We can understand efficiency and organisation—something for which Germany is well known—but when these skills are superimposed on a system that is designed to break the body and mind of the enemy, the result is terrifying. Is it possible that a regime known for its clinical barbarianism could have been inspired by a country like Canada—better known for its wheat fields, Rocky Mountains, and limitless opportunities?

Adolf Hitler was an artist and avid amateur historian before he became one of the biggest mass murderers in history. He was, along with millions of other Germans, a fan of the adventure stories of Karl May. Karl May’s books, still in print, have sold over two hundred million copies to date. May’s Winnetou novels detail adventures of a German surveyor (Old Shatterhand) and a noble Mescalero Apache. At the time, May was as popular as today’s J.K. Rowling or Stephen King. Hitler, as Fuehrer, is quoted (in Table Talk, a series of WWII monologues delivered by Hitler 1941-1944 recorded by Heinrich Heim, Henry Picker, and Martin Bormann) as saying “… I owe him [Karl May] my first notions of geography and the fact that he opened my eyes to the world. … I went on to devour at once the other books by the same author.” As Fuehrer, Hitler kept the entire May collection in his bedroom.

In Alan Gilbert’s article The Cowboy Novels that Inspired Hitler (in the Daily Beast.com), he quotes:

“Of Ukrainians, Hitler insisted, ‘There’s only our duty: to Germanize this country by the immigration of Germans, and to look upon the natives as Redskins.’ “

“To justify the slaughter of Poles, Hitler conjured North America: ‘I don’t see why a German who eats a piece of bread should torment himself with the idea that the soil that produces this bread has been won by the sword. When we eat wheat from Canada, we don’t think about the despoiled Indians.’ “

As a result of May’s works, Hitler was fascinated by all things connected to the North American “Indians” and the cowboys who tamed the Wild West. Of particular interest was the implementation of camps that contained the population of the Indigenous people. (In the United States, these holding areas are called Indian reservations; in Canada, they are called Indian reserves. Despite knowing they hadn’t reached India, Europeans continued to call Indigenous peoples Indians. Canadian legislation forces the continued use of this pejorative word by virtue of the Indian Act.)

When sifting through the archaeology of historical documents, it is impossible to point to any one action and say with certainty that Hitler did x because of y. What we can say is that he was drawn to the conflict of the American “Cowboy and Indian” and merged it with his twisted epic vision of an Aryan German Empire (aka Third Reich). For Hitler, it is difficult to say whether he drew any specific inspiration from Canada’s system of Indigenous containment. What is striking is how he adopted a similar methodology when processing prisoners in his Nazi camps as the Canadians employed in processing its Indigenous in their camps (ie. Indian Reserves combined with the Residential school system).

When Hitler sought to control the politicians and undesirables, he put them in concentration camps. At that time, there was no association with the death and genocide that we think of today. There was abuse in concentration camps as there is abuse in prison; there has always been and will likely always be. Concentration camps existed in Canada and the United States to intern the Japanese and Germans who might have been potential enemy combatants during the same war. The British in South Africa created concentration camps during the Boer Wars (1900-1902). This was just another name for a camp that was something less than a prison but more than house arrest or relying on the integrity of the person. It was the physical movement of people into a concentrated area to watch, educate, and discipline.

Although the United States government created concentration camps as early as 1838, the use of this method of internment became prevalent from the 1860s onwards as the borders of the United States moved ever westwards. The U.S. government referred to these concentration camps as Indian reservations. Reservations referred to land that the government had to set aside to house the ‘Indians’. Canada decided to force the assimilation of Indigenous people from its reserves. It concluded that basic education and training in physical work would make its Indigenous people productive members of Canadian society. Boys would be taught agriculture half a day and girls would be taught domestic chores half a day. The other half would be spent in the classroom. (The thinking was that they could increase labour without threatening the opportunity of European settlers.) In contrast, Nazi camps ensured that all able bodies were put to work—making toys, shoes, counterfeiting foreign currency, as well as munitions.

From before Canada was formed in 1867, the colonial government decided to begin a systematic assimilation of the Indigenous people with the stated objective of ‘taking the Indian out of the Indian’. A boarding school system called residential schools was thought to be the most effective way of washing away the unwanted cultures, languages, and customs. Children were taken from their families and placed in these residential schools (for most, year round). They were not allowed to speak their language, act ‘like Indians’ or even wear their familiar clothing.

It is difficult for us to imagine a world without the harrowing images of the Nazi concentration camps. Broken bodies, walking dead, and sallow eyes in striped prison outfits fill our mind’s eye. Forced labour, strict discipline, and winnowing rations kept the prison population in check. Names were replaced with numbers. Identities all but ceased in the camps. When the Russian and Allied forces liberated these places of death and disease, the world saw a glimpse into the deepest horrors of its collective heart. This was an unthinkable existence perpetrated in and by a modern, liberal European country against its own citizens as well as those it saw as its enemies. This was war.

Since WWII, we continue to witness atrocities perpetrated by nations against others, but few of this scale. Today, we hear of bombings (suicide and otherwise), beheadings, and other medieval-like inflictions by one group over another. We deem these groups outlaws and rogue states and terrorists. This is also the face of war, just updated.

Concentration Camps of Canada, draws attention to both the realities of the reserves where the Indigenous of Canada live to this day as well as the efforts by Canada to forcibly assimilate its one-time allies. The residential schools were not happy places for their pupils. Sadly, the usual sexual abuses existed and these grab the headlines. But the horror was the institutional backing of a policy recently deemed cultural genocide by both the United Nations and Canada’s Supreme Court Chief Justice Beverly McLachlin. It was a time where corporal punishment was the norm and these schools applied it to the point where it was considered abuse even for the times. Children were stripped of their ‘Indian’ name and given a number or a Christian name instead. They were constantly beaten—for speaking a language other than French or English, for doing anything considered ‘Indian’, and for not conforming to the Church-administered curriculum. Eighty thousand survivors of this system are still alive today (the last residential school was only shut down in 1996). Broken from reliving memories, many testified of the horrors to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. This commission published its report in 2015 where it concludes and agrees with the United Nations that Canada committed a sustained and systematic policy of cultural genocide. Where the Nazi camps lasted a little more than a decade, Canada’s continued for almost 150 years.

At the heart of the problem is poverty and a system that is too quick to give the benefit of doubt to those in power and too quick to dismiss concerns raised by those without.

Originally, Concentration Camps of Canada was envisioned as a text book with the main character (Migizi) demonstrating the multitude of injustices faced by Indigenous Canadians. Every element of Concentration Camps of Canada is based on the truth—gleaned from personal interviews as well as stories published by the official Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada 2015. The project was then winnowed into a story for brevity. Written for non-readers, it moves quickly and touches on matters that will, hopefully, resonate beyond the pages.

The story of Canada’s residential schools does not carry the shame history ascribes to Germany’s camps—nor should it. It is a terrible tragedy inflicted on a people who were subsequently forgotten by the world. If that statement were true, this subject would be closed. The truth of the matter is that the misguided approach that manifested itself in residential schools remains alive today in Canada’s treatment of Indigenous children through the Child and Family Services agencies. At present, we watch but rarely see the on-going damage to an already shattered culture.

To quote from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s executive summary at page 37 ff:

“It can start with a knock on the door one morning. It is the local Indian agent, or the parish priest, or perhaps, a Mounted Police officer. … There was a big truck. It had a back door and that truck was full of kids and there was [sic] no windows on that truck.” Larry Beardy travelled by train from Churchill, Manitoba, to the Anglican residential school in Dauphin, Manitoba—a journey of 1,200 kilometres.

… Campbell Papequash was taken, against his will, to residential school in 1946. “And after I was taken there they took off my clothes and then they deloused me. I didn’t know what was happening but I later learned about it, that they were delousing me; ‘the dirty, no-good-for-nothing savages, lousy.’”

…Murray Crowe said his clothes from home were taken and burned at the school that he attended in north-western Ontario.

… Gilles Petiquay, who attended the Pointe Bleus School, was shocked by the fact that each student was assigned a number. ‘I remember that the first number that I had at the residential school was 95. I had that number—95—for a year. The second number was number 4. I had it for a longer period of time. The third number was 56. I also kept it for a long time. We walked with the number on us.’

[at page 101 of the TRC] Discipline was ‘too suggestive of the old system of flogging criminals’. Children were chained together. In at least one instance, a boy was chained to his bed and flogged by the principal.

Abuse was not unreported. As early as 1886, Jean L’Heureux, a recruiter for the Roman Catholic Church, was accused of sexual abuse. No charges were laid. Over time, the government ignored and dismissed claims from the Indigenous alumni as baseless.

The schools were meant to cost the Canadian government nothing—as the forced child labour would generate income and the poorly paid missionaries kept overheads low. This model soon proved unsustainable and schools received a fixed amount per child. The unintended consequences was an increase of students who were too young or too sick to attend officially. This compounded the deaths. Official figures admit around 3,500 children dying while in care but unofficial figures estimate tens of thousands of children buried in unmarked graves—not too dissimilar to recent revelations about a care home run by Catholic nuns in Lanarkshire where at least four hundred (400) children are thought to be buried in a field without any markings. Or Ireland’s Tuam mother and baby home where Catholic nuns buried nearly eight hundred (800) babies and young children who died in their care—all in unmarked graves.

The Royal Mounted Police apologised in 2004 for its role in the residential schools. In 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada, Stephen Harper, issued a formal apology for the creation of the residential schools and the abuses carried out within it. All of the churches involved have apologised except the Catholic Church. The Pope has “… offered his sympathy and prayerful solidarity” for the Catholic Church’s role and abuses in the residential schools.

Nazis understood the role of their camps. On the surface, it provided a source of free labour, available subjects for their medical experiments, and a place to put dissidents without killing them outright (initially). The reality is that it formed a key component of Hitler’s strategy. His war was total—cultural, physical, and emotional. His objective was to cleanse Germany and the world of unwanted people (from Jews to Gypsies) and unwanted cultures. The camps have become synonymous with death but there were things worse than death—people being reduced to the living dead.

The consequence of the Nazis and WWII created a crisis of faith amongst Jews (and others). How could God allow such evil to be committed against his chosen people? Yet, three years after the last Nazi camp was liberated, the State of Israel was born.

For the Indigenous Peoples of Canada, the survivors have no land to return to. None of the reserves on which they live are theirs. Everything remains owned by Canada. They don’t even own their home on the reserve. Worse, they are not allowed by law to own their home or anything else on the reserve. For a policy that had its stated aim being assimilation, Canada failed to inculcate the most fundamental tenant of post-industrial modern existence—ownership and money.

War is all about subjugating your enemy’s will to your own. With the Nazis, everyone knew where they stood. With Canada, most of the world remains ignorant of the facts. There has been no Auschwitz-Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen moment in Canada where the world’s consciousness becomes aware of the plight of a people. No news reels would broadcast the images of troops liberating an emaciated people. Unlike Auschwitz-Birkenau or Bergen-Belsen, there would never be a liberation of Canada’s concentration camps.

-----------------------

*** If you are wondering who Duncan Scott was (pictured above), here is an exerpt from Wikipedia***

Prior to taking up his position as head of the Department of Indian Affairs, in 1905 Scott was one of the Treaty Commissioners sent to negotiate Treaty No. 9 in Northern Ontario. Aside from his poetry, Scott made his mark in Canadian history as the head of the Department of Indian Affairs from 1913 to 1932.

Even before Confederation, the Canadian government had adopted a policy of assimilation under the Gradual Civilization Act 1857. One biographer of Scott states that:

The Canadian government’s Indian policy had already been set before Scott was in a position to influence it, but he never saw any reason to question its assumption that the 'red' man ought to become just like the 'white' man. Shortly after he became Deputy Superintendent, he wrote approvingly: 'The happiest future for the Indian race is absorption into the general population, and this is the object and policy of our government.'... Assimilation, so the reasoning went, would solve the 'Indian problem,' and wrenching children away from their parents to 'civilize' them in residential schools until they were eighteen was believed to be a sure way of achieving the government’s goal. Scott ... would later pat himself on the back: 'I was never unsympathetic to aboriginal ideals, but there was the law which I did not originate and which I never tried to amend in the direction of severity.'[5]

while Scott himself wrote:

I want to get rid of the Indian problem. I do not think as a matter of fact, that the country ought to continuously protect a class of people who are able to stand alone… Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department, that is the whole object of this Bill.[7][8]

RSS Feed

RSS Feed